Rumi’s Revolution: Mawlana’s First Night of Dhikr-e Samâ’, Adapted from The Forty Rules of Love

The following account of Mawlana Jalaluddin Rumi’s first night of dhikr-e samâ’ has been adapted from the novel “The Forty Rules of Love”, by Turkish author Elif Shafak.

There are those who say that dancing is sacrilege. They think Allah gave us music—not only the music we make with our voices and instruments but the music underlying all forms of life, and then He forbade our listening to it.

Don’t they see that the entire universe is singing?

Life itself moves with a rhythm—the pumping of the heart, the flapping of a bird’s wing, the howling wind on a stormy night, a blacksmith working iron, the sounds of the womb surrounding an unborn babe… Everything partakes, passionately and spontaneously, in one magnificent melody. The dance of the whirling dervishes is a link in that perpetual chain. Just as a drop from the sea holds within it the secret of the entire ocean, our dance both reflects and shrouds the secrets of the cosmos.

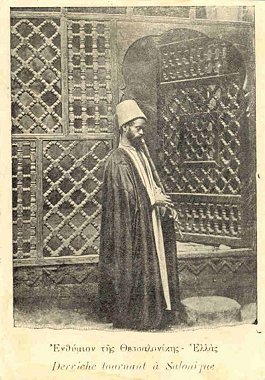

Shams of Tabriz in The Forty Rules of Love

Konya, June 1246

Hours before the performance, Mawlana Jalaluddin Rumi and Shams retreated into a quiet room to meditate. The six dervishes who were going to whirl in the evening joined them. Together they performed their ablutions and prayed the evening prayer. Then they donned their costumes.

Earlier they had talked at great length about what the proper attire should be and had chosen simple fabric and colors of the earth. The honey-colored hat symbolized the tombstone, the long white skirt the shroud, and the black cloak the grave. The dhikr-e samâ’ projects how Sufis discard the entire Self, like shedding a piece of old skin. Before leaving the hall for the stage, Mawlana recited a poem:

The gnostic has escaped from the five senses

And the six directions and makes you aware of what is beyond them.

With those feelings they were ready…

Pensively, Mawlana’s son, Sultan Walad, recalls the evening:

“Beauty is in the eye of the beholder,” Shams kept saying. “Everybody will watch the same dance, but each will see it differently. So why worry? Some will like it, some won’t.”

Yet on the evening of the dhikr-e samâ’, I told Shams I was worried that nobody would show up.

“Don’t worry,” he said forcefully. “The towns’ people might not like me, they might not even be fond of your father anymore, but they cannot possibly ignore us. Their curiosity will bring them here.”

And just so, the night of the dhikr, I found the open-air hall packed. There were merchants, blacksmiths, carpenters, peasants, stone-cutters, dye makers, medicine vendors, guild masters, clerks, potters, bakers, mourners, soothsayers, rat catchers, perfume sellers—even Sheikh Yasin had come with a group of students. Women were sitting in the rear. I was relieved to see the sovereign Kaykhusraw sitting with his advisers in the front row. That a man of such a high rank supported my father would keep tongues quiet. It took a long time for the members of the audience to settle down, and even after they had, the noise inside didn’t fully subside and there remained a murmur of heated gossip. In my itch to sit next to someone who would not speak ill of Shams, I sat next to Suleiman the Drunk. The man reeked of wine, but I didn’t mind.

My legs were jumpy, my palms sweaty, and though the air was warm enough for us to take off our cloaks, my teeth chattered. This night was so important for my father’s declining reputation. I prayed to Allah, but since I didn’t know exactly what to ask for, other than things turning out all right, my prayer sounded inadequate. Shortly there came a sound, first from far away, and then it drew nearer. It was so captivating and moving that all held their breath, listening.

“What kind of an instrument is this?” Suleiman whispered with a mixture of awe and delight.

“It is called the ney,” I said, remembering a conversation between my father and Shams. “And its sound is the sigh of the lover for the beloved.”

When the ney abated, my father, Mawlana, appeared onstage. With measured, soft steps, he approached and greeted the audience. Six dervishes followed him, all my father’s disciples, all wearing long white garments with large skirts. They crossed their hands on their chests, bowing in front of my father to get his blessing. Then the music started, and, one by one, the dervishes began to spin, first slowly, then with breathtaking speed, their skirts opening up like lotus flowers. It was quite a scene. I couldn’t help but smile with pride and joy. Out of the corner of my eye, I checked the reaction of the audience. Even the nastiest gossipers were attentive with visible admiration. The dervishes whirled and whirled for what seemed like an eternity. Then the music rose, the sound of a rebab from behind a curtain catching up with the ney and the drums. And that was when Shams of Tabriz entered the stage, like the wild desert wind. Wearing a darker robe than everyone else and looking taller, he was also spinning faster. His hands were wide open toward the sky, as was his face, like a sunflower in search of the sun.

I heard many people in the audience gasp with awe. Even those who hated Shams of Tabriz seemed to have fallen under the spell of the moment. I glanced at my father. While Shams spun in a frenzy and the disciples whirled more slowly in their orbits, Mawlana remained as still as an old oak tree, wise and calm, his lips constantly moving in prayer.

Finally the music slowed down. All at once the dervishes stopped whirling, each lotus flower closing up into itself. With a tender salute, my father blessed everyone onstage and in the audience, and for a moment it was as if we were all connected in perfect harmony.

A thick, sudden silence ensued. Nobody knew how to react. Nobody had seen anything like this before. My father’s voice pierced the silence. “This, my friends, is called the samâ’ —the dhikr of the whirling dervishes. From this day on, dervishes of every age will dance the samâ’. One hand pointed up to the sky, the other hand pointing down to earth, every speck of love we receive from Allah, we vow to distribute to the people.”

The audience smiled and mumbled in agreement. There was a warm, friendly commotion all over the hall. I was so touched by seeing this affirming response that tears welled up in my eyes. At long last my father and Shams were beginning to receive the respect and love that they most certainly deserved.

That first night of the dhikr-e sama’ could have ended on that warm note and I could have gone home a happy man, feeling confident that things were improving, had it not been for what happened next, ruining everything…

Enjoy the original narrative in the novel The Forty Rules of Love by Elif Shafak.